Sickle Cell Anemia

| Incidence | Sickle cell anemia affects about 100,000 people in the United States yearly and 1/500 African American births. It is more common in African Americans and specifically in locations such as sub-Saharan Africa, Saudi Arabia, India, and Spanish speaking areas of South America and Central America. |

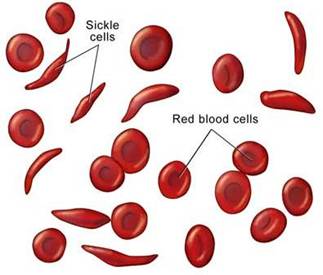

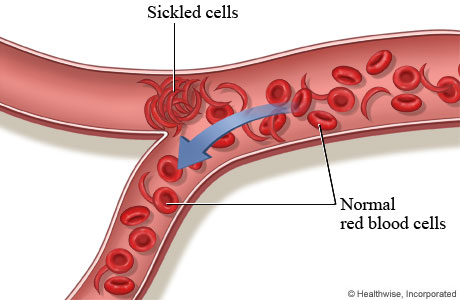

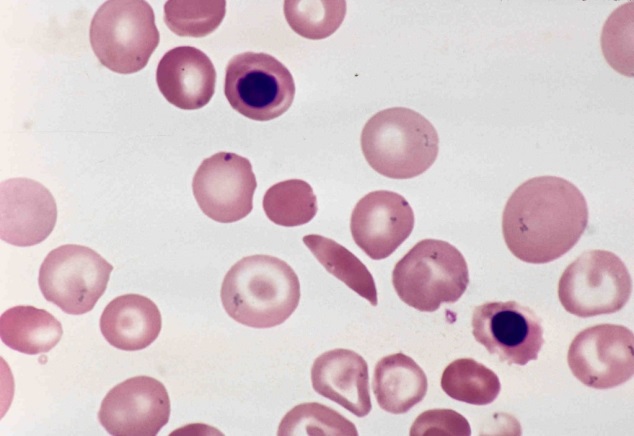

| Natural History |  Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited disorder which causes red blood cells to become “sickled.” Because of this, these sickled red blood cells have a difficult time moving through the blood vessels and cause occlusion of the vasculature. The vaso occlusion results in recurrent painful episodes called sickle cell crises. Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited disorder which causes red blood cells to become “sickled.” Because of this, these sickled red blood cells have a difficult time moving through the blood vessels and cause occlusion of the vasculature. The vaso occlusion results in recurrent painful episodes called sickle cell crises.

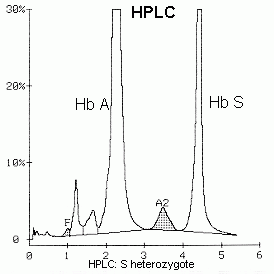

SCA a genetic disease that is caused by the substitution of a normal hemoglobin for hemoglobin S (HgS), which results in the above aforementioned sickled red blood cell. Valine is substituted for glutamic acid as the sixth amino acid in the beta globin chain, and this produces the faulty tetramer alpha 2 / beta S2. This type of hemoglobin is not able to deliver enough oxygen to tissues and also results in hemolysis (break down) of the red blood cell itself. Diagnosis is made by hemoglobin electrophoresis, which shows an increased level in hemoglobin S. If patients are homozygous (possess both genes/alleles, one from the mother and one from the father) for hemoglobin S, they are said to have hemoglobin SS. |

| Disease Presentation | Acute Pain Episodes

Treatment

|

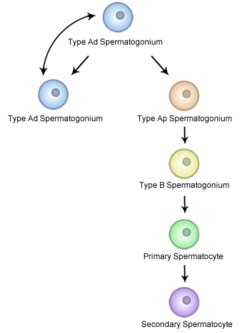

| Effect on Fertility | Sickle cell disease effects fertility in both males and females, but more often in males than in females. This is likely because of the delay in puberty (sexual maturation), priapism, and primary gonad dysfunction. In Agbaraji’s 1988 study, he found that there was an increase in abnormal spermatozoa indicating that sickle cell patients (25 of 50 patients) had more propensities for testicular dysfunction. There was also abnormality noted with the seminal vesicles and prostate gland, as the sickle cell patients had decreased ejaculate volume as well. In another study by Abudu, et al (2011), subjects with homozygous genes for Hemoglobin S have significantly lower testosterone than patients with normal hemoglobin A. Hemoglobin S patients then had a delay in onset of puberty and sexual development because of their lower testosterone. As a result, they had few sperm counts and had issues with fertility.

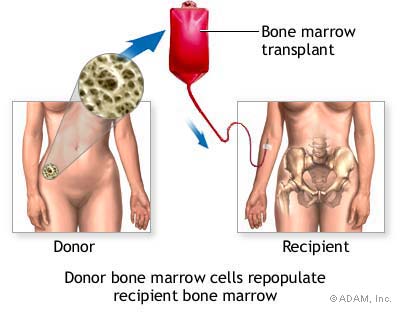

There has been no known negative effect on fertility that has been studied with hydroxyurea. However, this medication can cause both lymphoma and leukemia. These two types of malignancies may require chemotherapy. Thus, it would be beneficial to have fertility planning and consultation before administration of hydroxyurea in the event that a malignancy occurs as a side effect of this preventative treatment for sickle cell anemia. Because some of the refractory sickle cell anemia patients require stem cell bone marrow transplant, the effects on fertility must be discussed with this treatment as well. According to Tauchmanovà in his 2005 study on autologous bone marrow transplant and its effect on the endocrine system, 93% of women had precocious ovarian failure and 37% of men showed low testosterone levels after autologous stem cell transplant. Even after one year, semen analysis showed decreased sperm count in 91% of the males. Thus, with these decreased levels of hormones, fertility decreased in both males and females. Spermatogenesis and egg viability may also be a product of patient age and other associated factors while undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. According to Rovoa (2006), nine of the sixteen patients undergoing transplantation who were under twenty five did show some degree of spermatogenesis. |

| Fertility Preservation |  Since both males and females are at risk of infertility following bone marrow stem cell transplant, there are several fertility preservation options that should be discussed before treatment / transplant. According to Loren (2013), these patients at risk should undergo pretreatment counseling with individualization of fertility preservation depending on necessary foreseen treatment, patient age, time available, costs, and long term issues. Cryopreservation of embryos, oocytes, semen, and testicular tissue is a proven effective technique for preserving reproductive function. If possible, frozen embryos via invitro fertilization is also an option if the patient already has a spouse with plans for having a child. Since both males and females are at risk of infertility following bone marrow stem cell transplant, there are several fertility preservation options that should be discussed before treatment / transplant. According to Loren (2013), these patients at risk should undergo pretreatment counseling with individualization of fertility preservation depending on necessary foreseen treatment, patient age, time available, costs, and long term issues. Cryopreservation of embryos, oocytes, semen, and testicular tissue is a proven effective technique for preserving reproductive function. If possible, frozen embryos via invitro fertilization is also an option if the patient already has a spouse with plans for having a child.

For males with sickle anemia, cryopreservation of ejaculated sperm is well established technique and should be offered to all post-pubertal males. If the patient is unable to ejaculate or no sperm are found, they may recover sperm by epididymal sperm aspiration or testicular sperm extraction, as noted by Chan PT (2001). For patients who have known decreased fertility and problems conceiving, another option would be to use a gestational carrier and/or a sperm donor. Select a link below for more information about fertility preservation options: |

| Additional Considerations |  Because sickle cell anemia is a recessive genetic disease that can be passed down to future generations, patients may opt for genetic testing before becoming pregnant. If a mother and father are both only carriers (heterozygous) for the sickle cell trait, they have a 50% chance of having a son or daughter that is also a carrier with the trait and a 25% chance of having a child with sickle cell anemia/disease. If a mother and father both have sickle cell anemia/disease (homozygous), then they have a 100% chance of having a son or daughter with sickle cell anemia/disease. Some patients may choose not to conceive if they and/or their spouse have sickle cell anemia. Thus, it may be an option for these couples to see a genetic counselor before conceiving. According to Kuliev (2011), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of sickle cell anemia is an option for those who wish to continue only with pregnancies that are unaffected by sickle cell anemia. For PGD, the couple must use in vitro fertilization (IVF). Preimplantation embryos are biopsied and only the embryos without sickle cell anemia are selected. If HLA typing is done, unaffected embryos who are also HLA identical to an affected sibling can be selected for possible bone marrow stem cell transplantation of that sibling Because sickle cell anemia is a recessive genetic disease that can be passed down to future generations, patients may opt for genetic testing before becoming pregnant. If a mother and father are both only carriers (heterozygous) for the sickle cell trait, they have a 50% chance of having a son or daughter that is also a carrier with the trait and a 25% chance of having a child with sickle cell anemia/disease. If a mother and father both have sickle cell anemia/disease (homozygous), then they have a 100% chance of having a son or daughter with sickle cell anemia/disease. Some patients may choose not to conceive if they and/or their spouse have sickle cell anemia. Thus, it may be an option for these couples to see a genetic counselor before conceiving. According to Kuliev (2011), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of sickle cell anemia is an option for those who wish to continue only with pregnancies that are unaffected by sickle cell anemia. For PGD, the couple must use in vitro fertilization (IVF). Preimplantation embryos are biopsied and only the embryos without sickle cell anemia are selected. If HLA typing is done, unaffected embryos who are also HLA identical to an affected sibling can be selected for possible bone marrow stem cell transplantation of that sibling |

References:

Bunn, HF. “Pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease.” New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(11):762

Bainbridge, R., Higgs, D., Maude, G., Serjeant, G. “Clinical presentation of homozygous sickle cell disease.” Journal of Pediatrics. 1985;106(6):881

Rogers, Z., Wang, W., Luo Z., Iyer, R., Shalaby-Rana E., Dertinger, S., Shulkin, B., Miller, J., Files, B., Lane, P., Thompson, B., Miller S., Ware, R. “Biomarkers of splenic function in infants with sickle cell anemia: baseline datea from the BABY HUG Trial.” Blood. 2011;117(9):2614.

Tauchmanovà L, Selleri C, De Rosa G, Esposito M, Di Somma C, Orio F, Palomba S, LombardiG, Rotoli B, Colao A. “Endocrine disorders during the first year of autologous stem cell transplant.” Am J Med. 2005;118(6):664.

Chan P., Palermo, G., Veeck., “Testicular sperm extraction combined with intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the treatment of men with persistent azoospermia postchemotherapy.” Cancer. 2001; 92-1632.

Loren, A., Mangu, P., Beck, L., Brennan, L. “Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update.” Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013 July; 31(19):2500-10

Rovoa, T., Passweg J., Heim D., Meyer-Monard, S., Holzgreve W. “Spermatogenesis in long term survivors after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associatedwith age, time interval since transplantation, and apparently absence of chronic GVHD.” Blood. 2006. 108(3):1100.

Agbaraji, V., Scott, R., Leto, S., Kingslow, L. “Fertility studies in sickle cell disease: semen analysis in adult male patients.” Int J Fertility. 1988 Sep-Oct;33(3):347-52.

Abudu, E., Akanmu, S., et al. “Serum testosterone levels of HbSS male subjects in Lagos, Nigeria.” BMC Research Notes. August 2011, 4:298.

Kuliev, A., Pakhalchuk, T., Verlinski, O, et al. “Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for hemoglobinopathies.” Hemoglobin. 2011;35(5-6):547-55. Epub 2011 Sept 12

About The Author

Kristen Wendell, DO is completing her residency in internal medicine at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, IL. She received her undergraduate degree from the University of Illinois in Champaign/Urbana (2007) and her medical degree from Midwestern University / Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine (2013). As a healthcare provider with plans to complete a fellowship in hematology/oncology, she is working with the Oncofertility Consortium® team in order to provide awareness to other physicians regarding fertility preservation for patients with both malignant and non-malignant conditions.

Date of Completion: September 24th, 2014

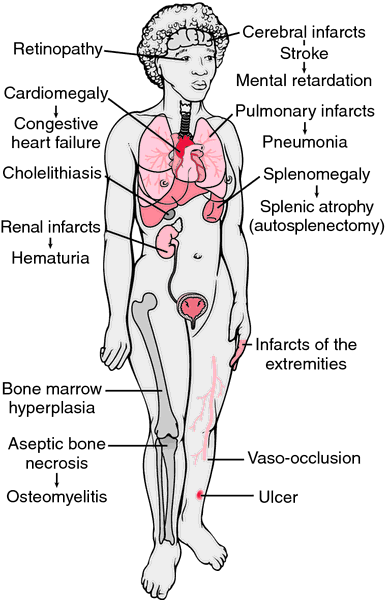

Vaso occlusion can occur in every single organ. Therefore, pain and complications are based on which organ is involved. These episodes usually last two to seven days, and are usually precipitated by infection, dehydration, altitude change, stress, menses, and alcohol. Accompanied signs/symptoms during these times may be fever, increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, high blood pressure, nausea, and vomiting. Listed below are some of the most common problems that occur as a result of sickling of the red blood cells and vaso occlusion of blood vessels.

Vaso occlusion can occur in every single organ. Therefore, pain and complications are based on which organ is involved. These episodes usually last two to seven days, and are usually precipitated by infection, dehydration, altitude change, stress, menses, and alcohol. Accompanied signs/symptoms during these times may be fever, increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, high blood pressure, nausea, and vomiting. Listed below are some of the most common problems that occur as a result of sickling of the red blood cells and vaso occlusion of blood vessels.

Lab Findings

Lab Findings

Semen analysis was done on 50 subjects (25 patients with sickle cell anemia and 25 control subjects with normal hemoglobin genotype). The ejaculate volume, sperm motility, sperm density, and normal sperm morphology were significantly reduced in the patients when compared with the control subjects. A significant increase was also observed in the percentage of spermatids and in abnormal spermatozoa with amorphous and tapered heads in the patients’ semen. These findings clearly show that there are definite abnormalities associated with semen in sickle cell anemia. Furthermore, they suggest that in addition to testicular dysfunction, there may be abnormalities in the accessory sex organs, such as the seminal vesicles and the prostate gland, particularly in view of the marked decrease in ejaculate volume of the patients.

Semen analysis was done on 50 subjects (25 patients with sickle cell anemia and 25 control subjects with normal hemoglobin genotype). The ejaculate volume, sperm motility, sperm density, and normal sperm morphology were significantly reduced in the patients when compared with the control subjects. A significant increase was also observed in the percentage of spermatids and in abnormal spermatozoa with amorphous and tapered heads in the patients’ semen. These findings clearly show that there are definite abnormalities associated with semen in sickle cell anemia. Furthermore, they suggest that in addition to testicular dysfunction, there may be abnormalities in the accessory sex organs, such as the seminal vesicles and the prostate gland, particularly in view of the marked decrease in ejaculate volume of the patients.