Picture by Alison Kim, PhD

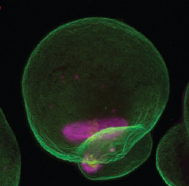

Many people have never heard of the term parthenote, the byproduct of a process called parthenogenesis. Parthenogenesis occurs when an egg becomes activated and starts dividing without sperm. While parthenogenesis happens frequently in many plants and vertebrate animals, it is less common in mammals. In mammals, this cell division progresses abnormally and eventually stops. Continued division can cause a parthenote to become a tumor or even cancer. During human parthenogenesis, the egg only has half the normal amount of genetic material so it does not form an embryo and will never become a baby.

Interestingly, scientists developing new fertility methods could benefit from parthenogenesis. Current fertility preservation methods include egg and embryo cryopreservation. However, prepubescent girls and women with an immediate need for treatment may choose ovarian tissue cryopreservation, which instead involves a short surgical procedure. In ovarian tissue cryopreservation, the ovary is removed, frozen, and a portion is reimplanted into the cancer survivor when she is ready to get pregnant.

Unfortunately, ovarian tissue cryopreservation is not recommended for women with blood-born cancers, such as lymphoma, or those in localized to the pelvis, because reimplanting the ovary may also reintroduce the cancer. Research at the Oncofertility Consortium is developing a technique called in vitro egg maturation, which entails removing developing eggs from an ovary, and growing them in culture. Once the eggs are mature, they could be fertilized and the resultant cancer-free embryo transferred to a survivor’s uterus.

What is the relationship between parthenogenesis and in vitro egg maturation? Once scientists mature eggs in a laboratory, they need to determine if the eggs are healthy enough to start dividing. Studies in animal models can examine the viability of eggs through fertilization. Since the federal government does not fund research that produces human embryos, parthenogenesis could be an alternative to deduce the health of eggs. A human egg grown in culture could be activated with chemicals to determine if in vitro maturation is successful enough to use as a fertility preservation technique.

Unfortunately, the same law that prevents federal funding to make human embryos also prevents parthenogenesis in federal research-even though these cells will never become human embryos. This means that when scientists develop in vitro egg maturation, they have no way to determine the viability of such eggs, except in clinical trials, which would have a significantly greater financial and emotional toll on patients.