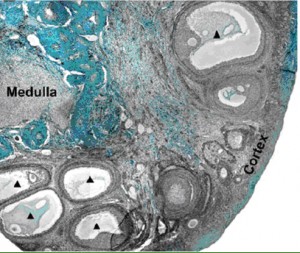

A section of a baboon ovary from the Xu et al. paper

Many women who preserve their reproductive potential prior to fertility-threatening cancer treatments currently choose ovarian stimulation and subsequent banking of their eggs or fertilized embryos. Unfortunately, women who choose these techniques must delay cancer treatment for up to three weeks. During that time, injectable hormones help mature follicles within the woman’s ovaries to produce oocytes which then become eggs that are retrieved during an outpatient surgery. Since some women are not able to delay chemo- or radiation therapy, there is a need for fertility preservation that does not require hormone stimulation.

Experimental techniques such as ovarian removal and tissue banking can provide an opportunity for women to have children. One caveat of ovarian tissue banking is the risk of reintroducing the cancer when the ovary is transplanted back into the cancer survivor. Given this, researchers at the Oncofertility Consortium are developing ways to mature ovarian follicles in vitro, outside a woman’s body. Once these advances are made ovarian tissue may be removed, the follicles matured in vitro, and then go through traditional in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques without the risk of reintroducing any cancer cells.

A recent publication by Min Xu et al. at the Oncofertility Consortium highlights advances in the in vitro culture of ovarian follicles and maturation of those follicles into oocytes. While some of these techniques are successful in rodents, the translation to non-human primates, such as baboons, has made less progress. The article, “In Vitro Oocyte Maturation and Preantral Follicle Culture from the Luteal Phase Baboon Ovary Produce Mature Oocytes,” describes how researchers are able to use the developing cells within an ovary to produce oocytes.

In the ovary, the more developed oocyte precursors, called cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs), lay underneath the outer region of the tissue, called the cortex. Xu was able to remove these COCs and mature them in vitro to produce oocytes. COCs with more layers of support cells surrounding them were more likely to mature in vitro and up to one quarter of the oocytes were then able to be fertilized by baboon sperm and begin dividing. In addition, Xu was able to remove the less mature follicles from the interior of the ovaries and culture them with a specialized growth system called a fibrin-aliginate matrix (FAM). The high-tech FAM provides support to the growing follicle but can also partially degrade and allow the follicle to expand in size as it develops into a COC. The researchers also examined the effect of follicle stimulating hormone during this growth. The detailed work published in the Biology of Reproduction provides a framework to produce new needed fertility preservation techniques for women who undergo fertility-threatening cancer therapy.

Read the entire Xu et al. article.