Francesca Duncan, PhD

———

Applying emerging Assisted Reproductive Techonology (ART) procedures in an Oncology setting may help cancer survivors attain their desire to have a child spared of the very cancer that they themselves battled. Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) is a prenatal screen performed prior to the initiation of pregnancy. In this procedure, cell(s) from embryos derived from ART procedures (either in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection) are biopsied and used for genetic testing so that only unaffected embryos are transferred to the recipient uterus. Since its inception in the 1990s to screen for sex-linked disorders, PGT has been used to screen embryos for a wide range of abnormalities including single gene disorders, chromosomal abnormalities, and aneuploidies. More controversial uses of PGT include HLA-typing, sex selection for family balancing, and screening for non-medical genetic traits. PGT has a 2% misdiagnosis rate and is generally considered to be successful. Approximately 7,000 cycles of PGT have been reported worldwide, resulting in more than 1,000 live births.

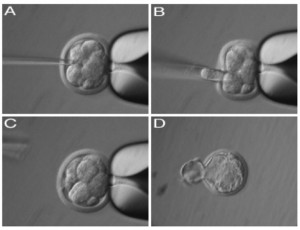

Image: Process of PGD resulting in a healthy, hatched embryo Francesca Duncan

In the past few years there has been an increasing use of PGT to screen for cancer syndromes because the five-year survival rate for most cancers is improving for reproductive-aged men and women. Thus, starting a family post-cancer is becoming a reality for many. Furthermore, strides in basic research have uncovered the genetic links to many cancers, therefore allowing a technology such as PGT to be applied to this disease. According to a 2006 paper published by Dr. Kenneth Offit and colleagues in the Journal of the American Medical Association, there are 55 published reports of using PGT to screen for 22 common cancer predisposition syndromes including hereditary breast, ovarian, and colon cancers (1). Of the thirteen PGT centers that provide clinical or research services, nine perform cancer-related screening.

Although using PGT to screen for cancer predisposition syndromes could be a promising option for Oncofertility patients seeking to start a healthy family, caution needs to be exercised before making it standard for several reasons. First, although the embryos selected for implantation may not harbor specific genetic mutations that will predispose the children to cancer, the embryos may have other genetic defects that were not screened for. Second, it is important to realize that many cancers are sporadic, so PGT will not offer a protective benefit against these forms. Finally, PGT has only been in existence for about twenty years, so we do not know the effects of this procedure on the long-term health and well-being of the offspring. Studies in mice have demonstrated that simply culturing embryos in vitro can have subtle but statistically significant consequences on the gene expression profiles, imprinting, and long-term behavior in the resulting animals (2-4). In contrast, my work using a mouse model of PGT demonstrates that removing a single cell from an 8-cell embryo does not affect the global patterns of gene expression in the resulting blastocyst (5). Although these results are encouraging for demonstrating the safety of PGT, they are still preliminary and more research needs to be done.

(1) K Offit et al. JAMA (2006); 296: 2727-2730.

(2) P Rinaudo et al. Reproduction (2004); 128: 301-311.

(3) AS Doherty et al. Biology of Reproduction (2000); 62: 1526-1535.

(4) DJ Ecker et al. PNAS (2004); 101: 1595-1600.

(5) FE Duncan et al. Fertility Sterility (2009); 91: 1462-1465.