Uterine Fibroids

| Prevalence |

Uterine fibroids, also known as myomas or leiomyomas, are the most common pelvic tumor in women of reproductive age1. They are found in approximately 80% of hysterectomy specimens2. |

| Risk Factors |

Incidence rates are found to be two-to-three fold greater in African American women, compared to Caucasian woman1,3. One study showed that estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids of any size by age 50 was greater than 80% for African American women and 70% for Caucasian women1. The etiology of increased incidence in African Americans is unknown. Additional risk factors include early menarche, nulliparity4, early exposure to oral contraceptives (one study showed 13-16 years old)5, diet rich in red meats and alcohol, vitamin D deficiency6, hypertension, obesity, and/or history of sexual or physical abuse7. Ovulation induction agents are not linked to fibroid growth8. Caffeine is not a risk factor, and smoking is associated with actual reduced risk due to an unknown mechanism. Several specific karyotype abnormalities have also been reported. As an example, in Caucasian women, a specific polymorphism in the transcription factor HMGA2 appears to be linked to uterine leiomyomas and shorter adult height9. |

| Natural History |

Uterine fibroids are benign monoclonal tumors arising from smooth muscle cells of the myometrium. They are generally associated with pre-menopause, as their incidence parallels the life cycle changes of the reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone. Prospective studies have found that between 7 to 40 percent of fibroids regress over a period of six months to three years10,11. However, there is wide variation in the growth of individual fibroids within each woman. There is further increasing evidence of postpartum regression of fibroids12. Most women experience shrinkage of fibroids at menopause, though postmenopausal hormone therapy may cause continued symptoms in some. Fortunately, hormone therapy does not typically lead to the development of new fibroids13. Symptoms are also often dependent on fibroid location and type of estrogen preparation. For example, submucosal fibroids and transdermal estrogen (in some studies) are associated with a higher risk of clinical symptoms after menopause14,15. |

| Clinical Manifestations |

Symptomatic uterine fibroids generally fall under 3 distinct categories: 1. Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding (most common): thought to be secondary to abnormalities of uterine vasculature, impaired hemostasis, or molecular dysregulation of angiogenic factors18. Intruding submucosal and intramural fibroids are commonly associated with significant bleeding19. 2. Pelvic pressure and pain: typically secondary to mass compression of surrounding organs of the urinary and/or GI tract. Very large uteri may further compress the inferior vena cava and increase risk of thromboembolism20. 3. Reproductive dysfunction: distortion of the uterine cavity can result in difficulty conceiving a pregnancy, can increase risk of miscarriage, and has been associated with other pregnancy complications, such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, malpresentation, and preterm labor and birth21. |

| Effect on Fertility | Uterine fibroids can lead to infertility in 1-2 percent of women19. Proposed mechanisms include interference with implantation, uterine distention, or contractility21,22.

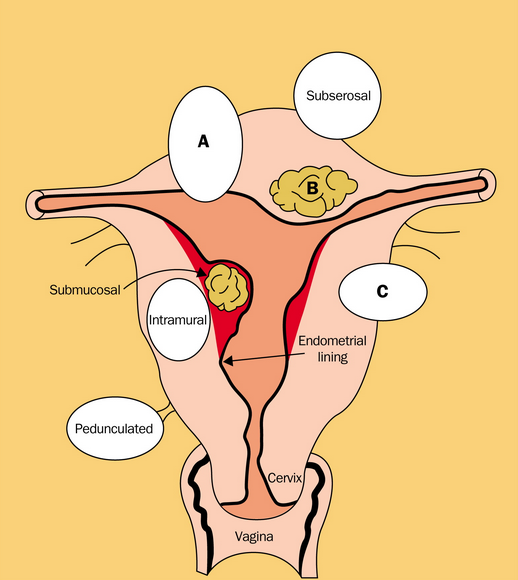

Fibroids are often described according to their location in the uterus (see Figure 1). Those that distort the uterine cavity are more likely to impact fertility, as well as in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes22,28. For example, women with submucosal or intramural fibroids that protrude into the uterine cavity are found less likely to become pregnant with increased risk of spontaneous abortion. Fibroids in other locations, such as near a fallopian tube ostium or near the cervix, may impede fertilization as well. Subserosal fibroids, in contrast, do not affect fertility outcomes16. In regards to IVF outcomes, one study demonstrated that having an intramural fibroid essentially halves the chance of an ongoing pregnancy following assisted conception26,27. Figure 1: Location of uterine myomas. Submucosal fibroids intrude into or are contained in the uterine cavity. Intramural fibroids are contained within the wall of the uterus. Subserosal fibroids create the characteristic irregular feel of the myomatous uterus. Most myomas are of mixed type, however, as illustrated by A, B, and C17.

Therefore, fibroids should be ruled out in any woman presenting with infertility, and removal may become necessary prior to achievement of a pregnancy. However, it should be noted that certain fibroid treatments can subsequently impact future pregnancy. Uterine artery embolization (UAE), for example, has higher rate of miscarriage and preterm delivery, compared to myomectomy. UAE also appears to increase rate of delivery by cesarean section23. Thus, myomectomy is the preferred surgical therapy for women who wish to conceive. It has been shown that magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery may also serve as a better alternative for women wishing to conceive, compared to UAE29. For women who are pregnant with fibroids, most do not experience fibroid-related complications24. Almost 90 percent of fibroids detected in the first trimester will regress in total fibroid volume upon reevaluation at three to six months postpartum25. |

References

-

Buttram Jr, V. C., and R. C. Reiter. “Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management.” Fertility and sterility 36.4 (1981): 433.

-

Cramer, S. F., and A. Patel. “The frequency of uterine leiomyomas.” American journal of clinical pathology 94.4 (1990): 435-438.

-

Templeman, Claire, et al. “Risk factors for surgically removed fibroids in a large cohort of teachers.” Fertility and sterility 92.4 (2009): 1436-1446.

-

Baird, Donna Day, and David B. Dunson. “Why is parity protective for uterine fibroids?.” Epidemiology 14.2 (2003): 247-250.

-

Marshall, Lynn M., et al. “A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata.” Fertility and sterility 70.3 (1998): 432-439.

-

Baird, Donna Day, et al. “Vitamin D and the risk of uterine fibroids.”Epidemiology 24.3 (2013): 447-453.

-

Baird, Donna, and Lauren A. Wise. “Childhood abuse an fibroids.”Epidemiology 22.1 (2011): 15-17.

-

Stewart, Elizabeth A., and Andrew J. Friedman. “Steroidal treatment of myomas: preoperative and long-term medical therapy.” Seminars in reproductive endocrinology. Vol. 10. No. 4. Thieme, 1992.

-

Hodge, Jennelle C., et al. “Uterine leiomyomata and decreased height: a common HMGA2 predisposition allele.” Human genetics 125.3 (2009): 257-263.

- Peddada, Shyamal D., et al. “Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105.50 (2008): 19887-19892.

- DeWaay, Deborah J., et al. “Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata.”Obstetrics & Gynecology 100.1 (2002): 3-7.

- Laughlin, Shannon K., et al. “Pregnancy-related fibroid reduction.” Fertility and sterility 94.6 (2010): 2421-2423.

- Yang, C. H., et al. “Effect of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women—a 3-year study.” Maturitas 43.1 (2002): 35-39.

- Akkad, Andrea A., et al. “Abnormal uterine bleeding on hormone replacement: the importance of intrauterine structural abnormalities.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 86.3 (1995): 330-334.

- Sener, A. B., et al. “The effects of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women.” Fertility and sterility 65.2 (1996): 354-357.

- Casini, Maria Luisa, et al. “Effects of the position of fibroids on fertility.”Gynecological endocrinology 22.2 (2006): 106-109.

- Stewart, Elizabeth A. “Uterine fibroids.” The Lancet 357.9252 (2001): 293-298.

- Stewart, Elizabeth A., and Romana A. Nowak. “Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era.” Human reproduction update2.4 (1996): 295-306.

- Buttram Jr, V. C., and R. C. Reiter. “Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management.” Fertility and sterility 36.4 (1981): 433.

- Shiota, Mitsuru, et al. “Deep-vein thrombosis is associated with large uterine fibroids.” The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine 224.2 (2011): 87-89.

- Pritts, Elizabeth A., William H. Parker, and David L. Olive. “Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence.” Fertility and sterility91.4 (2009): 1215-1223.

- Klatsky, Peter C., et al. “Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 198.4 (2008): 357-366.

- Carpenter, T. T., and W. J. Walker. “Pregnancy following uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: a series of 26 completed pregnancies.”BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 112.3 (2005): 321-325.

- Segars, James H., et al. “Proceedings from the Third National Institutes of Health International Congress on Advances in Uterine Leiomyoma Research: comprehensive review, conference summary and future recommendations.”Human reproduction update (2014): dmt058.

- Laughlin, Shannon K., Katherine E. Hartmann, and Donna D. Baird. “Postpartum factors and natural fibroid regression.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 204.6 (2011): 496-e1.

- Eldar-Geva, Talia, et al. “Effect of intramural, subserosal, and submucosal uterine fibroids on the outcome of assisted reproductive technology treatment.” Fertility and sterility 70.4 (1998): 687-691.

- Khalaf, Y., et al. “The effect of small intramural uterine fibroids on the cumulative outcome of assisted conception.” Human Reproduction 21.10 (2006): 2640-2644.

- Hart, Roger, et al. “A prospective controlled study of the effect of intramural uterine fibroids on the outcome of assisted conception.” Human Reproduction 16.11 (2001): 2411-2417.

- Rabinovici, Jaron, et al. “Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids.” Fertility and sterility 93.1 (2010): 199-209.

About the Author

Melody Besharati is a medical student at the University of California, Irvine. Inspired to be a physician after working with her research mentor in the field of adolescent oncology, Ms. Besharati carries a passion for patient advocacy. In medical school, she created treatment and wellbeing summaries for cancer patients and has written educational text for patients to empower them during interactions with their healthcare providers. Her research interests include improving young adult community access to important quality of life resources, including fertility preservation. She is currently working with Dr. Teresa Woodruff on a related study, which culminated from a research rotation at Northwestern University. Ms. Besharati has applied for the 2014-2015 Residency Match, in the field of Obstetrics and Gynecology.