Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

| What is Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)? |

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory condition comprised of two major disorders: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD). These disorders have distinct yet overlapping pathologic and clinical characteristics; however, their pathogenesis remains poorly understood. |

| Prevalence and Incidence |

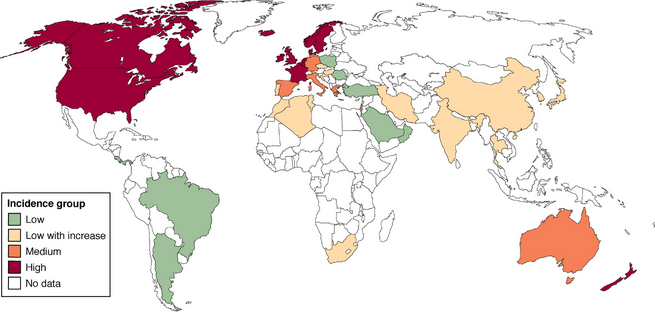

Today, CD prevalence is roughly equivalent to that of UC in both North America and Europe. One of the largest North American studies, based on health insurance data from 9 million subjects, calculated CD prevalence to be 201 and UC prevalence to be 238, estimating more than 1.3 million adults with IBD in the United States2. IBD incidence appears to be lower in South America, Asia, and the Middle East (see Figure 1)3,4; however, there appears to be a steady rise in incidence of IBD during the last few decades, highest among adolescents and young adults with peak onset of 15-35 years of age13. Women, in general, have a 20-30% higher risk of developing CD, though no such gender difference is observed for UC.

|

| Disease Course | The disease course in UC can be described in terms of disease activity, number of relapses, surgical history, and mortality. With treatment, the course of UC typically consists of intermittent exacerbations that alternate with long periods of remission. Inflammation is limited to the mucosal layer of the colon and may commonly involve the rectum. Approximately 67 percent of patients experience at least one relapse within 10 years of diagnosis. Approximately 20 to 30 percent of patients will require colectomy for acute complications or for medically intractable disease14. Long-term complications of UC include strictures, dysplasia, and colorectal cancer. The risk of colorectal cancer appears to be highest in patients with pancolitis, with risk being shown to increase 8 to 10 years into diagnosis15. Overall mortality appears to be highest in the first year after ulcerative colitis diagnosis, though these rates have decreased over time16.

In CD, inflammation is characterized as transmural and can affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the perianal area, which leads to a spectrum of clinical manifestations more variable than that of UC. Although anatomical distribution is fairly stable over time, the behavior of the disease may vary significantly with passing time. For example, a French study17 looking at various CD phenotypes found nonstricturing or nonpenetrating types in 70% of patients, stricturing in 17%, and penetrating in 13%. At 10 year follow-up, 27% and 30% of nonstricturing types had transformed to stricturing and penetrating disease, respectively. Approximately 10-30% of CD patients experience relapse or disease exacerbation after the first year of diagnosis. At 10-15 years following, 13% will have a relapse free course, 20% will have annual relapses, and 67% will have a chronic intermittent course18. Most patients with CD ultimately require surgery, with risk for hemicolectomy at approximately 35% after 10 years from diagnosis19. Recurrence of perianal fistulas after medical or surgical therapy is common. Given disease heterogeneity, overall life expectancy in patients with CD is not well established. |

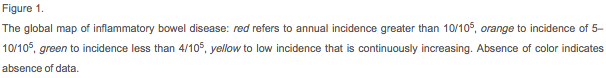

| Clinical Manifestations | Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of the most common clinical, biochemical, and pathological features distinguishing UC from CD5.The systemic nature of IBD disease is an important consideration for both UC and CD patients. Extra-intestinal manifestations associated with IBD are identifiable in approximately 10 percent of patients at presentation and up to 30 percent of patients within the first few years following diagnosis29. These manifestations tend to occur more commonly with colonic involvement.

Inflammatory arthropathies are the most common extra-intestinal manifestations in IBD patients with prevalence between 7-25%. Other common complications include hepatobiliary disease; cutaneous manifestations which can include granulomatous perianal/peristomal ulcers or fistulas, reactive erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosom, acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to nutritional deficiency (namely, zinc); ocular manifestations such as anterior uveitis, cataracts, or glaucoma (due to drug exposure); increased risk of osteoporosis, osteopenia, thromboembolism, and anemia; and nephrolithiasis, among many others28. Therefore, IBD not only affects bowel but practically every other organ via various mechanisms. Treatment of underlying disease becomes essential here, in addition to adequate treatment of all additional manifestations to maintain patient health and quality of life.

|

| Effect on Female Fertility |

Women with inactive IBD appear to have fertility equivalent to the general population9. A recent study investigating ovarian reserve status in woman with CD by serum AMH levels found that subjects did not have severe ovarian reserve alterations compared with the control population21. Reasons for low birth rates among these women are likely secondary to psychological factors and/or are treatment-related. As an example, voluntary “childlessness” and patient self-overestimation of IBD-related reproductive risks has been reported as one cause for reduced fertility rates among IBD patients. Concerns about fertility seemed highest among women with CD and a history of disease-related surgery20. While IBD itself has not been found to impact fertility, it is the active inflammation, medications, and/or surgeries associated with the disease that can negatively affect female fertility:

|

| Conception and Pregnancy Outcomes | Disease activity at the time of conception is found to influence the course of pregnancy for women with IBD. Data shows that women with UC are more likely to have disease activity during pregnancy than women with CD, which may be a reflection of cytokine production of the placenta and subsequent impact on UC24,25. Most significantly, patients who conceive when disease is in remission are expected to experience a normal course of pregnancy. In contrast, those who conceive at time of active disease are much more likely to face continued symptoms throughout pregnancy, with up to 70% experiencing relapse and/or further deterioration26. Thus, conception at a time of remission is most advised. Pregnant women with IBD further have increased risk for antepartum hemorrhage, low birth weight infants, and premature deliveries; however, risk of congenital abnormalities do not appear to be increased12. Cesarean delivery is advised for women with history of IPAA or with active perianal disease at time of delivery6.

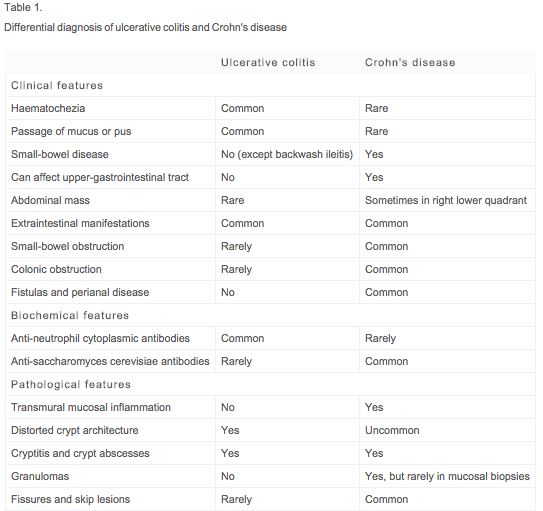

Table 2 describes profiles for various IBD medications used during pregnancy and breastfeeding to maintain remission9.

|

| Effect on Male Fertility |

Like women, men with IBD in remission do not appear to have decreased fertility compared with the general population30. However, fertility and sexual function in these patients are similarly affected by psychological factors, disease activity, medications, and a history of IBD-related surgery. Depression, for example, is one psychological factor that can affect patients with IBD, and use of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications may subsequently lead to erectile dysfunction. Additional adverse effects of IBD treatment on sexual function and male fertility are as follows:

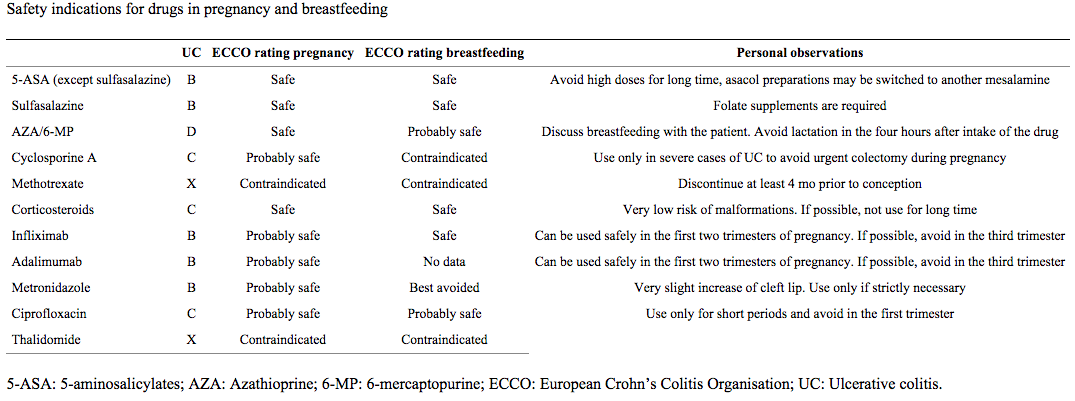

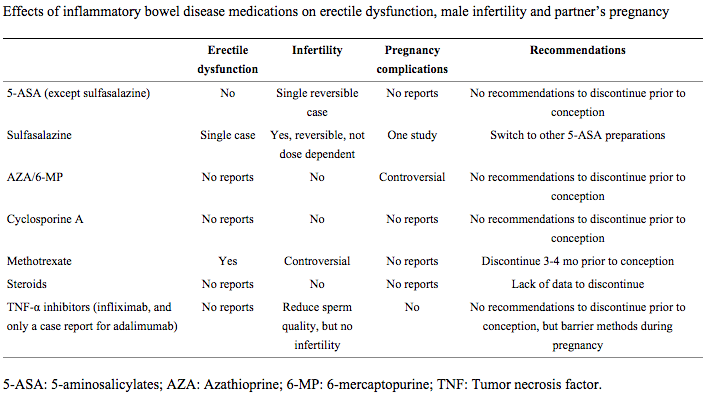

Table 3 reviews male side effect profiles for different IBD medications9.

|

References

- Khalili, Hamed, et al. “Geographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US women.” Gut 61.12 (2012): 1686-1692.

-

Kappelman, Michael D., et al. “The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States.” Clinical gastroenterology and Hepatology 5.12 (2007): 1424-1429.

-

Molodecky, Natalie A., et al. “Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review.”Gastroenterology 142.1 (2012): 46-54.

-

Cosnes, Jacques, et al. “Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases.” Gastroenterology 140.6 (2011): 1785-1794.

-

Baumgart, Daniel C., and William J. Sandborn. “Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies.” The Lancet 369.9573 (2007): 1641-1657.

-

Van Assche, Gert, et al. “The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations.” Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 4.1 (2010): 63-101.

-

Oresland T, Palmblad S, Ellström M, Berndtsson I, Crona N, Hultén L. Gynaecological and sexual function related to anatomical changes in the female pelvis after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994;9:77–81.

-

Asztély M, Palmblad S, Wikland M, Hultén L. Radiological study of changes in the pelvis in women following proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1991;6:103–107.

-

Palomba, Stefano, et al. “Inflammatory bowel diseases and human reproduction: A comprehensive evidence-based review.” World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 20.23 (2014): 7123.

- Ahmad G, Duffy JM, Farquhar C, Vail A, Vandekerckhove P, Watson A, Wiseman D. Barrier agents for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000475

- Tavernier, N., et al. “Systematic review: fertility in non‐surgically treated inflammatory bowel disease.” Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 38.8 (2013): 847-853.

- Cornish, J., et al. “A meta-analysis on the influence of inflammatory bowel disease on pregnancy.” Gut 56.6 (2007): 830-837.

- Langholz E., Munkholm P., Nielsen O.H., Binder V. (1991) Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in Copenhagen county from 1962 to 1987. Scand J Gastroenterol 26: 1247–1256

- Solberg, Inger Camilla, et al. “Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study).” Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 44.4 (2009): 431-440.

- Levin, Bernard. “Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer.” Cancer 70.S3 (1992): 1313-1316.

- Jess, Tine, Morten Frisch, and Jacob Simonsen. “Trends in overall and cause-specific mortality among patients with inflammatory bowel disease from 1982 to 2010.” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 11.1 (2013): 43-48.

- Luis E., Collard A., Oger A.F., Degroote E., Aboul Nasr El Yafi F.A., Belaiche J. (2001) Behaviour of Crohn’s disease according to the Vienna Classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut 49: 777–782

- Loftus E.V., Jr, Schemed P., Sandborn W.J. (2002) The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn’s disease in population based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 16: 51–60

- Cosnes J., Cattan S., Blain A., Beaugerie L., Carbonnel F., Parc R., et al. (2002) Long-term evolution of disease behaviour of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 8: 244–250

- Mountifield R, Bampton P, Prosser R, Muller K, Andrews JM. Fear and fertility in inflammatory bowel disease: a mismatch of perception and reality affects family planning decisions. Inflamm Bowel Dis.2009;15:720–725.

- Fréour T, Miossec C, Bach-Ngohou K, Dejoie T, Flamant M, Maillard O, Denis MG, Barriere P, Bruley des Varannes S, Bourreille A, et al. Ovarian reserve in young women of reproductive age with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1515–1522.

- Şenateş E, Çolak Y, Erdem ED, Yeşil A, Coşkunpınar E, Şahin Ö, Altunöz ME, Tuncer I, Kurdaş Övünç AO. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels are lower in reproductive-age women with Crohn’s disease compared to healthy control women. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e29–e34.

- Olsen KO, Joelsson M, Laurberg S, Oresland T. Fertility after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in women with ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:493–495.

- Mahadevan, Uma, et al. “865 PIANO: a 1000 patient prospective registry of pregnancy outcomes in women with IBD exposed to immunomodulators and biologic therapy.” Gastroenterology 142.5 (2012): S-149.

- Pedersen, N., et al. “The course of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective European ECCO‐EpiCom Study of 209 pregnant women.” Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 38.5 (2013): 501-512.

- Riis L, Vind I, Politi P, Wolters F, Vermeire S, Tsianos E, Freitas J, Mouzas I, Ruiz Ochoa V, O’Morain C, et al. Does pregnancy change the disease course? A study in a European cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1539–1545

- Villiger, Peter M., et al. “Effects of TNF antagonists on sperm characteristics in patients with spondyloarthritis.” Annals of the rheumatic diseases (2010).

- Danese, Silvio, et al. “Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease.” World Journal of Gastroenterology 11.46 (2005): 7227.

- Monsen, U., et al. “Extracolonic diagnoses in ulcerative colitis: an epidemiological study.” The American journal of gastroenterology 85.6 (1990): 711-716.

- Selinger CP, Eaden J, Selby W, Jones DB, Katelaris P, Chapman G, McDondald C, McLaughlin J, Leong RW, Lal S. Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy: lack of knowledge is associated with negative views. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e206–e213.

- Timmer A, Bauer A, Dignass A, Rogler G. Sexual function in persons with inflammatory bowel disease: a survey with matched controls. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:87–94.

- Lampiao F, du Plessis SS. TNF-alpha and IL-6 affect human sperm function by elevating nitric oxide production. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17:628–631.

- Taffet SL, Das KM. Sulfasalazine. Adverse effects and desensitization. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:833–842.

- Moody GA, Probert C, Jayanthi V, Mayberry JF. The effects of chronic ill health and treatment with sulphasalazine on fertility amongst men and women with inflammatory bowel disease in Leicestershire. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:220–224.

- Di Paolo MC, Paoluzi OA, Pica R, Iacopini F, Crispino P, Rivera M, Spera G, Paoluzi P. Sulphasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid in long-term treatment of ulcerative colitis: report on tolerance and side-effects. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:563–569.

- Kjaergaard N, Christensen LA, Lauritsen JG, Rasmussen SN, Hansen SH. Effects of mesalazine substitution on salicylazosulfapyridine-induced seminal abnormalities in men with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:891–896.

- Xu L, Han S, Liu Y, Wang H, Yang Y, Qiu F, Peng W, Tang L, Fu J, Zhu XF, et al. The influence of immunosuppressants on the fertility of males who undergo renal transplantation and on the immune function of their offspring. Transpl Immunol.2009;22:28–31.

- Thomas E, Koumouvi K, Blotman F. Impotence in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate. J Rheumatol.2000;27:1821–1822.

- Rubin PC. Prescribing in pregnancy. London: BMJ Books; 2000.

- Hueting WE, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Sexual function and continence after ileo pouch anal anastomosis: a comparison between a meta-analysis and a questionnaire survey. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:215–218.

- Prideaux L, De Cruz P, Ng SC, Kamm MA. Serological antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1340–1355.

About the Author

Melody Besharati is a medical student at the University of California, Irvine. Inspired to be a physician after working with her research mentor in the field of adolescent oncology, Ms. Besharati carries a passion for patient advocacy. In medical school, she created treatment and wellbeing summaries for cancer patients and has written educational text for patients to empower them during interactions with their healthcare providers. Her research interests include improving young adult community access to important quality of life resources, including fertility preservation. She is currently working with Dr. Teresa Woodruff on a related study, which culminated from a research rotation at Northwestern University. Ms. Besharati has applied for the 2014-2015 Residency Match, in the field of Obstetrics and Gynecology.